Happiness: vital forces aligned along lines of excellence in a life of scope. Aristotle

Last week I spent the day in a corner room on the 40th floor of the New York Academy of Science at the 2nd annual TEDxNYED convocation, summit, gathering, choir.

Ironies abounded. Breathtaking 360 degree views of lower Manhattan. Inside, the NY educators sat in the dark, windows shuttered, tethered to chairs, looking at a wall, a lecturer, a screen.

Was it Plato’s cave? Was this an illusion, or enlightenment?

Or Foucault‘s vision of institutional life, realized. Where was Jeremy Bentham‘s Panopticon?

For me, it was merely day 6 in an airless classroom. My customary routine.

No matter. It was an uplifting day. It isn’t often that I am invited to be a member of a live audience for a TV show. There hasn’t been much glitter in my 30 years of professional life.

Aside: Although there were many references to education reform, public policy, access and opportunity, the room did not reflect the diversity that was so passionately invoked.

Side reflection: In a historically gendered profession, it is always interesting to note the disproportionate number of males who hold the leadership positions in the field of education, schools, and schooling. Steve Bergen called them DWMs, “despicable white males.”

I first heard Alan November in 1996. He came to the independent school where I taught to speak to the faculty about technology. We’d just become a 1:1 laptop school. His prediction: within 10 years, everyone would have a web page. Guess he had foresight.

The following year Heidi Hayes Jacobs conducted a workshop for the faculty. She presented a PowerPoint on curriculum mapping to an awed faculty. From that day forward, we vowed that we all wanted to make presentations as sleek and efficient. She’s still making presentations to awed faculty with new, re-purposed words.

Side query: Why does the field of education ruminate and regurgitate and masticate at such a glacial pace. We’re all talk. How come no one has ever invoked radical change to topple such an intractable system?

“Upgrades,” says Hayes-Jacobs. Upgrade the old content, skills, assessment. Upgrade to new structures, too, for scheduling, student and personnel groupings, physical spaces.

Re-assess the common core and improve it. Re-imagine assessments. What makes a quality tweet, blog post, wiki? Hayes-Jacobs encourages teachers to share subversive practices, and upgrade.

“Re-search,” she says. I thanked Hayes-Jacobs for re-introducing that word. As a literature and humanities teacher, I tend to value academic terms like “research” and “scholarship,” over “projects,” “activities,” and PBL. Our librarian supports teachers and guides students through the research process, using NoodleTools and online scholarly subscription databases.

Side reflection: Why | wherefore all the acronyms in education? PBL. PLN. PLC. AP. IEP. GT. LLD. STEM. STEAM.

Is this because teaching is such an undervalued vocation that we need to resort to bytes and branding to attract consumers? But our consumers are the next generation, and isn’t it our moral responsibility to “teach your children well?”

Gary Stager expressed passionate ideas about harnessing children’s intensity. Yes, we understand this.

Fourteen additional talks with slide decks continued at the front of the room. The TEDx format is edu-tainment. As teachers, we rarely have a wide audience. We’re pretty much in the shadows, performing every day, stars in tiny orbits. The TED brand reclaims a bit of sparkle.

It’s quite pleasant to be at a pep rally for education. So what if the TED talks are reductive and boiled down. I’m still working out the TAP. [Acronym: Task, Audience, Purpose.] Who is the audience for TEDxNYED? What is the purpose of these video talks?

And though “A little learning is a dangerous thing,” perhaps the friendly TED brand counteracts a lot of ignorance, which is equally dangerous.

But none of this really matters to me.

Because what I do every day take place in an airless corner room, inside an institution, on a hill, removed from the world.

I have made the choice to root my social activism in the moment, and there is no need to look far afield. There is no need for mic or lights or camera to be a humanizing force, minute by minute, in an intractable system.

My daily practice is infused with mindfulness, attention to all kinds of cues, inspired by high standards, and conveyed with love. It is about inwardness, cultivating deep thinking. Not about showmanship and the stage. There is laughter and joy.

I love going to work each morning.

TEDxNYED was a pleasant interlude. Hopefully the conversation about education will continue in the foreground while we daily engage in the work of educating the next generation. The back channel.

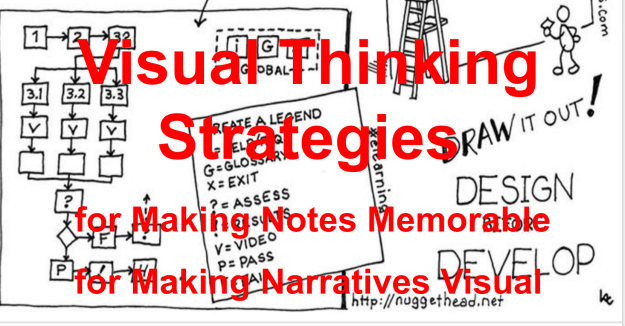

So here’s what’s really on my mind. There is a new taxonomy that extends Bloom’s framework of cognition. It’s an upgrade.

It is called the Taxonomy of Significant Learning. Dee Fink is the designer. And I believe this is an idea worth spreading.

I learned about L.Dee Fink from my PLC. Backwards design for a high school teacher necessitates having a long view, a look at successful college and university models, and beyond. Not on my watch will students be “academically adrift.”

What kinds of skills and expertise do students need in order to be successful in higher education, in real and online work spaces, as collaborators, global citizens, and caring human beings?

It was gratifying to read about the University of Virginia Med School’s exhilarating new prescription for teaching and learning. UVA’s Rx for Learning highlights student-centric round table learning in a flattened classroom infused with technology. This is the type of blended learning that colleagues are introducing in innovative primary and secondary school classrooms everywhere.

Fink’s system underscores the human dimension of learning, and focuses on integrated design principles. I plan to use this taxonomy as the foundation for next trimester and the close of a year. I am always fascinated by what students retain.

To think about:

How can I encourage student conversations about their learning styles, about what works and what doesn’t work?

What are the important, big concepts | categories | ideas | skills that I would like students to retain? Why?

What will students be able to do with the content or skills they’ve learned in my classes?

Where is the value? If “knowledge is in the group” (NYSAIS motto), how has this year with me as guide contributed to students’ academic and social-emotional development? How have they learned to learn in more effective and deeper ways, so that they can connect with other people in the world?

I discovered that my very conscientious students were taking too many notes in classes. Word by word, page after page, they were reproducing the transcript of an entire Harkess discussion, rather than noting key ideas.

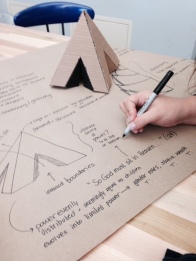

I discovered that my very conscientious students were taking too many notes in classes. Word by word, page after page, they were reproducing the transcript of an entire Harkess discussion, rather than noting key ideas. And then I booked a session in the Makerspace.

And then I booked a session in the Makerspace.